A Way You Have to Be!

(Washington High

School, St. Paul, Minnesota, 1963-'65)

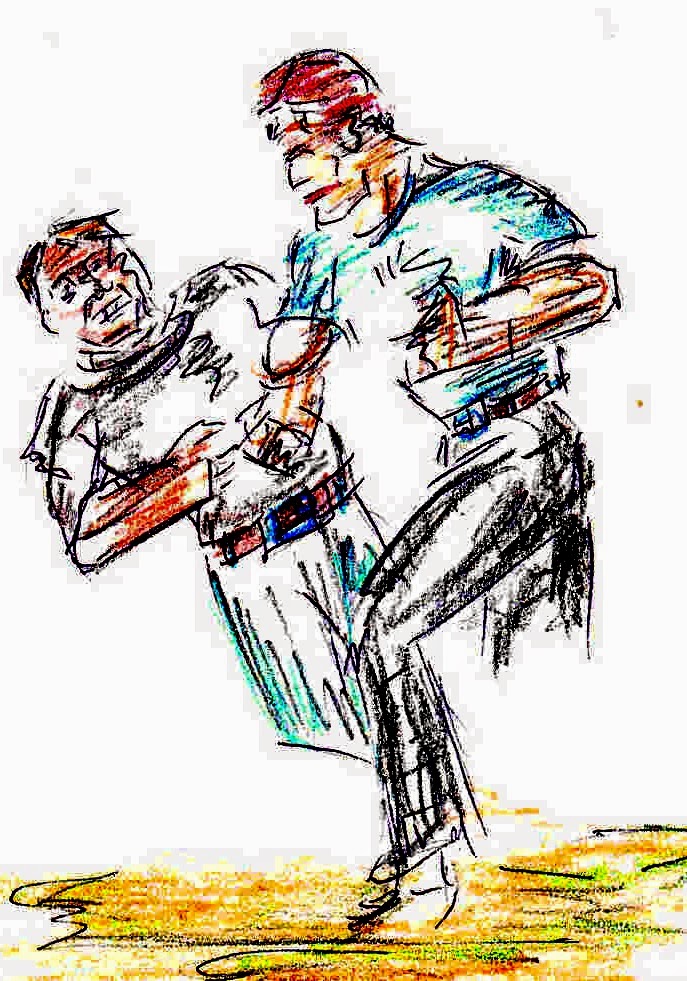

When he saw me standing in line, the senior—myself being a sophomore at the time—it wasn’t about

anything in particular, something about wanting to get ahead of me in the lunch

line, in the cafeteria, and then he and I started fighting, he had tried to

push his way in-between me and the guy ahead of me, and in the process pushing

me backwards, and he pushed me backwards in a hostile way, and I dragged him

out of the line like a ragdoll, I had

been weightlifting back then, I had muscles coming out of my ears, and fingers

and toes, and nose, much less biceps, and I overturned him concluded and onto

one of the tables, then leaning over him, knee on his chest, and about to

hammer on his face, decided in the clap of an eye, in choking him, thus, with

both hands curled around his roaster like neck, I was clogging his breathing,

per near knock him out cold, lest I kill

him I let up. Everybody was too stunned

to pull me off him, or fearful, or perhaps it was entertaining, he was the bully

sort; and he was about my weight, and my height, nearly the same built, but

surly with not nearly the strength. He couldn’t have gotten loose if he wanted

to, I had knocked all the fight out of him, when his back hit the table—like a

hammer hitting an anvil. When I let up on him, he couldn’t swallow, he sounded

hoarse. I hurt him bad: the show was over.

Well, I went back

to the line, regained my composure, and there were plenty of kids looking at

him and me, when he said, “It’s not fair a sophomore should get away with

this,” to his friends. I made a turnabout while down near the food counter at

this time, and said, “What did you say?” and I believe he replied, “I don’t know,

all right!” And he was all right, but with plenty of bruises I’d think, and

quite rough looking, sounding like a frog with a rustic tone to his voice; by

and large, he was on guard, not looking for a rematch, but perhaps wishing his

friends would back him up, and they didn’t.

I sat down and ate

my food off my tray, with Bill, a friend from the neighborhood, and nobody came

after me; I had plenty of friends from my neighborhood too, who were also tough,

and my brother was a senior there, and by and by I would have gotten even, and

Bill was a fighter too.

It was late, and

everyone had left the cafeteria, except me, who sat at a corner table, trying

to calm myself down some, an electric light overhead. I didn’t care if I’d go

late to class, matter of fact, I didn’t care if I ever went back to class.

In those days

(1963-'65), the principals, or at least at Washington High School, in St. Paul,

Minnesota, were all very strict. You may not believe this, but he wanted to

punish me and not the perpetrator the one who started it all, it was my second

fight, that year, and he wanted to expel me from school, with the exception of, allowing

me back in a week.

My brother got word

of the incident, and accompanied me to the principal’s office, —which I really didn’t

want to do—save, he wanted to have his say-so, and as for me, I was done with

the mess, and really didn’t care if I ever went back to school or not; when I

had confirmed with Mike what I considered, the good news, that, yes, I was

going to be expelled, he got angry—not at me, but the situation, and it took a

lot for him to get angry in those days, he wasn’t a hothead like me, but it got

his goat, that the other kid got off scot-free, this also was a hot peeve.

When we walked in

together, into the Principal’s office, he had been standing there previously by

his desk, he saw us, and then sat himself down in a chair against the wall—we

had no invitation: amused eyes, indexed book opened, as if he was giving some

word a diagnoses, some deep thought, had been pacing the floor just beforehand,

would be a good guess. My brother said, as if he had already accessed as to the

treatment being given me, “You live in a different world than we do, Mr.

Principle, we live down in a rough neighborhood, you should visit it sometime,

then you’d know we don’t let people push us around, my brother Chick, was

simply standing his ground.” (Most everyone referred to me back then as Chick,

not Dennis.)

The simplicity and directness of my

brother’s disapproval constituted almost a hurt to the principle: so

unexpectedly made himself accessible. I had no sense the principle was on the

defensive, this was no game. And there was some satisfaction to the additional

knowledge, he was acquiring.

“Well,” said the

principal, rotating his chair to the over-heated, radiator, as if in thought (knowing good and well he had

let the other kid off lightly):

“The other lad, said he started the fight, and your brother didn’t disagree!”

“Yes, I suppose you

could say that, but did you ask him why he started it?”

“Why…? I wasn’t

there.”

But Mike was

determined to get his point across, whether he liked it or not, either way, it

was coming out.

“What’s the matter

with you, you don’t let people push you out of the lunch line because they feel

like it, and allow them to bully you, and how would my brother look letting

this joker push him around so everyone can see, and you don’t run to the

principle for such matters…?”

“Is that what

happened?” asked the principal, in disarray.

“There’s nothing

wrong with the way my brother’s supposed to be! You would have simply let the

bully, bully him.”

“I’m sorry,” said the principal (ere, he yielded) “but I think we do understand each other, or perhaps

I want to, your brother was quiet on some of these facts, therefore, I’ll

simply give him a letter of reprimand, and he can bring it home, have your

mother sign it, and we’ll forget the suspension. But this is a warning, you do your

fighting elsewhere!”

I

never had the right words back then, so perhaps my silence, or deletion of the

facts, distorted the facts for the principle, he did not have a full

description, picture, whatever the case, mother never found out about it, I

simply signed the note, and returned it to the office the next day. Actually, I

had singed all her notes back then, had I let her sign it, they would have

figured it was a forgery.

I suppose as I look back on this, the

principle had closed sympathetically on this matter. And as I walked out of his

office, as I looked over to greet my brother’s eyes, I’m sure he could see in

mine surprise and delight. Kind of like saying, ‘Boy ain’t this cool though,”

but I didn’t say that, I didn’t say anything. I think my hands were even a

little moist, and I wiped my forehead dry, then dried my palms on my trousers a

second time. I didn’t like that kind of confrontation back in those days. I’d

had rather fought than confront, but I did seemingly breathe better through my

skin, I guess, perhaps that’s a good sign of health, so I’d learn later on in

life, that is to say, your body is healthy, because I felt full of oxygen,

ready for combat if need be. But somehow I was sweating’ more than usual now. “Funny,

ain’t it,” I thought, what verbal challenging can cause, per near

hyperventilation. Perhaps there was some booze seep out of me likewise, I did

my share of night drinking, too!

“Go on back to your class tomorrow” Mike

urged after a delicious moment of silence.

“Go on,” he insisted, “I’ll see you in

the neighborhood,” and I went to my locker and got my items: jacket and so

forth, and went about my way.

No:

1022 (9-15 & 16-2014)